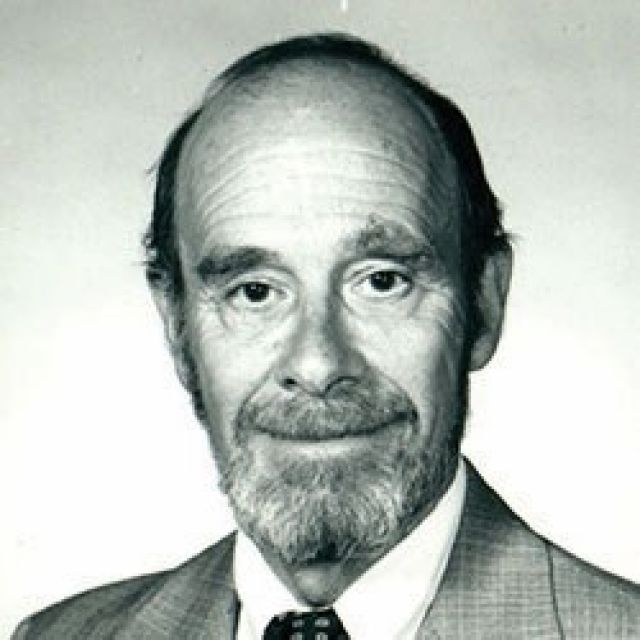

Bill Dulaney

Retired journalism professor and creator of the School of Journalism internship program

Anyone who’s ever had an internship in the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications, or will someday, owes a tip of the hat to Bill Dulaney, a retired journalism professor who died in March 2019. He was 89.

The internship program we all know today was born in the School of Journalism in the College of the Liberal Arts in the early 1970s. At the start, the focus was on print journalism majors at newspapers in Pennsylvania. Bill proudly displayed a map in his office with stickpins showing where the internships were.

Every summer Bill would drive around the state to see how the interns were doing. One intern recalled that at lunch he gave her advice that becalmed her starry-eyed vision of journalism and introduced her to the realities of the newsroom. She had complained because the editor had suppressed some negative stories. “Welcome to the real world,” she recalled Bill replying. He was not the kind of person to sugarcoat anything.

Others remember how tough he was — or seemed to be. Jan Corwin Enger said she overslept one day and arrived late for class, only to be greeted by the “stink eye.”

“I’ve been setting multiple alarms ever since,” she said.

Other students recall how he would advise those not cut out for journalism. “Son, I suggest you find another path to glory.” Or: “You ought to find some other way to make a living.” Or: “There are plenty of other worthwhile professions for you, but you can’t write so journalism is not among your options.”

His most oft-repeated line, remembered on Facebook after he died: “All writing should be clear, concise and interesting.”

Bob Frick managed to sneak into the beginning newswriting class as a freshman. After giving Bob the stare but letting him remain, Bill went on to say: “Now, this may seem like a crowded class, but maybe half of you will still be here in a month.” Chuck Hall recalled, “Drill camp, almost literally.”

Many students credit Bill with making them good writers and good reporters. Brian Healy said he owes much of his writing skills to Bill. “He was a demanding teacher with high standards. I was a recipient of the Dulaney stare and that slow talking rebuke for sloppy work. Yet he also had a wicked sense of humor.”

Probably unknown to many was Bill’s role in helping create the Native American Press Association. In fact, about five weeks before he died, one of the association’s first members, Tim Giago, wrote about Bill in a column. The title of the column is: “Paying tribute to the man who cheered Native journalists on.”

Bill got his first college degree from The Citadel, a military college in South Carolina, and went on to become a crypto officer in the U.S. Navy, serving three years in then French Morocco. His son, Billy, was a career sailor.

Meanwhile, his daughter, Carol, said she is now sorting through Bill’s estate of first-edition books and antiques. Carol and Bill are his only survivors. His wife, Marge, died nine days after he did.

From a map of Pennsylvania with stick pins designating internship sites, Bill Dulaney’s efforts have grown to the point where there’s now a three-person staff for internships in the Bellisario College, led by an assistant dean who tracks on a spreadsheet more than 450 a year from all majors.