King of 'The Hot Seat'

Faculty member Steve Manuel enjoys helping students succeed — and making them a little uneasy too

Faculty member Steve Manuel enjoys helping students succeed — and making them a little uneasy too

IN THE SPRING OF 2005, Michael Robinson called two of his Penn State teammates with a proposal. Both players, Tamba Hali and Alan Zemaitis, had studied communications just like Robinson, the popular Nittany Lions quarterback.

“Guys, want to go sit in and check out this wild class I heard about?” he asked.

“Uh, no, actually,” they replied. Like any good college students, extra classes sounded like … extra classes.

But Robinson kept making his case. The class was a public relations course taught by longtime Bellisario College associate teaching professor Steve Manuel. Robinson loves Manuel, a former Marine who completed a 28-year decorated career as a military spokesperson before coming to Penn State.

Robinson had heard reports about a specific, dreaded assignment called “The Hot Seat” that sounded an awful lot like what football players had to sit through after a bad loss or critical mistake.

“You gotta come with me,” Robinson told Hali and Zemaitis. “Every student has to get up and deal with the media and answer a bunch of really hard questions. And you know who gets to ask the questions? We do!”

Robinson is a charismatic speaker and leader, a big reason why he has become a prominent voice that you can see on the NFL Network’s “Good Morning Football” on a regular basis. And so, Hali and Zemaitis eventually said sure, they’d go with Robinson. (’04 Journ, ’06 Ad/PR).

Now Robinson just had one more tiny little detail to sort out: He hadn’t actually asked Manuel if he could crash the class.

A student prepares to take their turn in "The Hot Seat."

STEVE MANUEL NEVER LIKED SCHOOL. Like, he really didn’t like school. He still remembers how angry his parents were when they asked him what happened to his algebra book in junior high school. He had to sheepishly tell them that he hated algebra and was struggling with it and he didn’t really know what to do with all the frustration he was feeling so … he had buried the textbook in the backyard.

It wasn’t that he got bad grades or wasn’t popular—he did fine, both with academics and with his peers. He was a good athlete who was student council president and had plenty of friends. But he didn’t like it very much. He’s a slow reader, and his backyard algebra graveyard is Exhibit A of how he feels about math. So when he talks about getting good grades but despising being a student, he sounds like one of those guys who’s really good at unclogging toilets but doesn’t want to be a plumber. School just wasn’t for him.

And yet, go figure: Somehow he’s become a beloved member of academia at Penn State. But that’s where life took him after his lengthy military career. He’d joined the Marine Corps at age 17, as a 5-foot-7, 125-pound human javelin, and he thrived. Manuel loved the military life—he’s a fun, opinionated person with a serious artistic streak as a longtime sports photographer, but he also has a significant part of his personality that appreciates the disciplined, straightforward rigors and rewards that the military presented. He liked how military life often didn’t have many gray areas. There were standards he had to live up to, and it was up to him whether he lived up to them or not. It’s the same way he teaches—he tells students what they need to do, teaches them how to do it, and then it’s up to them if they do it or not.

When active duty was over, Manuel built a successful career as a public affairs officer for the Marines and for the Secretary of Defense. He ended up seeing large swaths of the planet, ranging from Vietnam and Okinawa to Hawaii, Cuba and Afghanistan.

He’d married his wife, Jaylene, in 1973, and she’d gone on the wild, globe-trotting ride with her husband for two decades. They’d originally met on a blind date, went to a Tiny Tim concert a week later and got married the next month at the Justice of the Peace. (In case you’re struggling to keep reading because your eyebrows are still raised about the Tiny Tim concert, you should know they both loved it. “He played the ukulele and sang, and it was great,” Manuel says.)

By the mid-1990s, with four kids who wanted to anchor down somewhere, Manuel got an opportunity to come back to Penn State and teach PR, and it felt like a great fit. It has been.

Even from his first days on campus, Manuel’s courses were built like him and liked by students because they were like him. Eighteen years later, his approach remains consistent. He still loves teaching, and at age 70 he’s planning to do it for the foreseeable future. He’d always said he wouldn’t teach past 70, and says he enjoys his photography, playing tennis, hanging out with his grandkids, and making tiffany lamps and stained-glass windows in his spare time. “If I don’t like a movie, I get up and leave,” he says. “When I don’t enjoy this anymore, that’s what I’ll do. I don’t need to do this. I do it because I love it.”

There’s still something about teaching that gets into his bloodstream. He still loves gathering with young people eager to learn. He still loves challenging them, doing Hot Seats, being tough but fair. He still loves using the first week of classes to post on the big screen behind him the most embarrassing social media images and posts from students in the class. His point: If he can find those images and words, so can future employers.

Steve Manuel was elected by students as a member of the Faculty Homecoming Court in 2007.

It’s not always easy passing Manuel’s classes. But he sure is memorable. “I interact with thousands of Bellisario alums, and Steve’s in the top three that people talk about,” says Mike Poorman, director of alumni relations for the Bellisario College. “That’s the highest compliment you can pay to a professor. It can be years and years since they've been in Carnegie Building, but they all seem to remember Steve.”

Manuel’s founding principle of public relations is one of the founding principles of him: Tell the truth, even if the truth hurts. On a phone call discussing his life and career, Manuel parachutes into the middle of a question that included a mention of the concept of “spin” in the PR field. “You know, spin is a four-letter word,” Manuel says. “It’s a fancy way of lying. It really is. You can’t spin bad news. Bad news is bad news. If you’ve done something wrong, own it. There will be pain. But it won’t be as painful, for as long, if you own it.”

He began agitating as early as his first year on campus that Penn State should be teaching crisis communications, which is essentially how to deal with really bad news. Actually, it’s worse than really bad: Manuel believes every business, every school, every nonprofit should have a plan for horrific news, the kind that nobody wants to make a plan for but is, according to Manuel, much more likely than CEOs and PR flaks want to even consider. Or, as Manuel himself describes it: “Crisis communications isn’t what is bad for business. It is what will end your business.”

In his view, every business—including Penn State—has a handful of catastrophic things that can happen in which some smart group of people should have spent some time working through, even if it is stashed away in a vault somewhere. Do most businesses think like Manuel? Nope. “The thing you hear is, ‘That stuff always happens to the other guys, to the other company, to the other school,’” Manuel says. “Those businesses are virtually guaranteed to completely botch handling any kind of bad news. It’s not the real world.”

It took years of Manuel agitating, but he eventually got his wish and the school greenlit a crisis communications course. The first year he offered it, Manuel had 25-30 students. But enrollment spiked past 100 students the next few years as word spread quickly about the uniqueness of the class, how challenging it could be, and how Manuel was interesting and blunt and funny and tough, sometimes all within the same sentence. Manuel eventually realized that the ballooning number of students had diminishing returns, saying it turned an intimate experience into a lecture class, so he has kept it at its original size for the past 10 years or so. “I want kids to have a hands-on experience,” he says.

And nothing has been better for business than rumors of a certain assignment from the class. An assignment so tense, so difficult, so oh my god, maybe PR isn’t for me after all, that it had to be seen to be believed.

Its name? The Hot Seat.

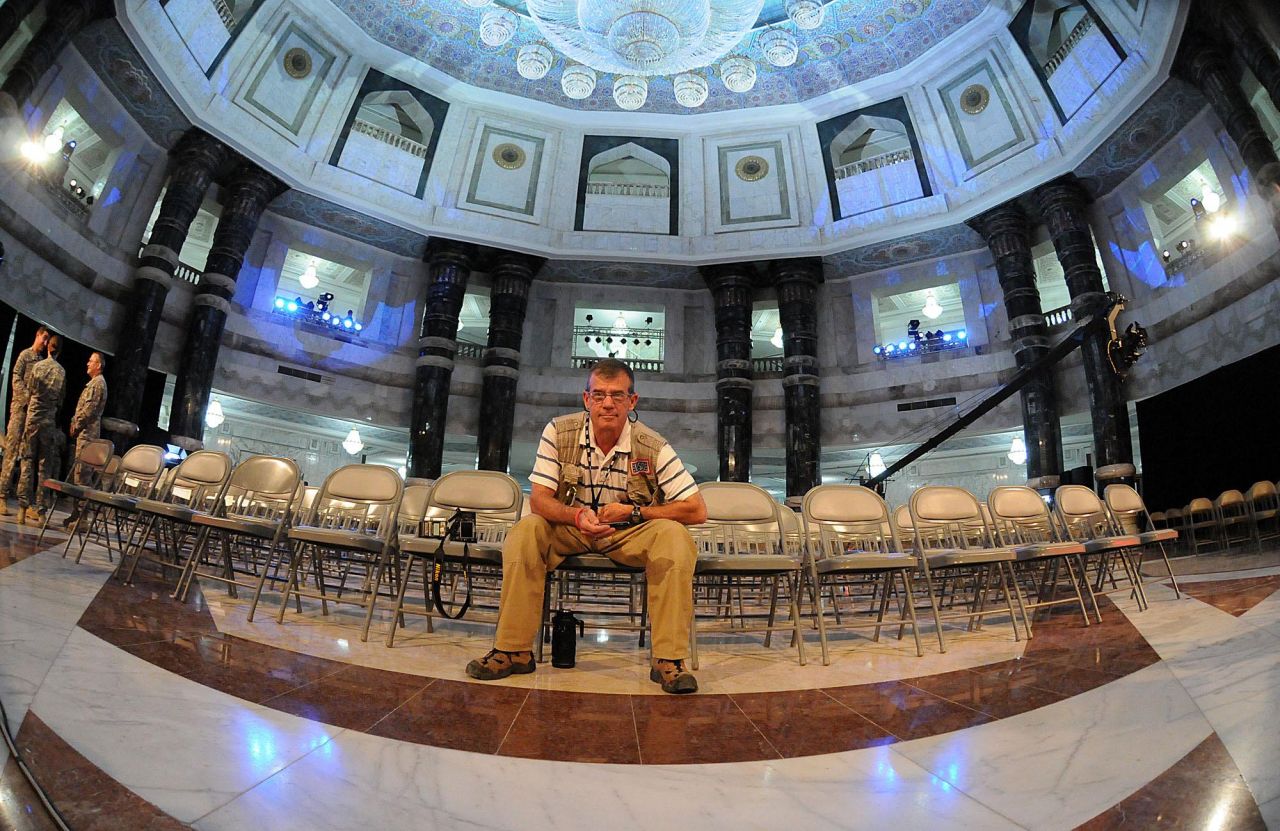

Steve Manuel poses for selfie as he takes a break from his duties as official photographer on a USO tour featuring Stephen Colbert and Dane Cook in 2009.

WHEN ROBINSON CALLED MANUEL, he’d already taken a class or two with him and gravitated toward Manuel. Oddly enough, he liked how unimpressed Manuel was with him, the star athlete who had 100,000 people screaming his name every Saturday. “I was the quarterback at Penn State,” Robinson says. “So, lots of people didn’t challenge me to be the best version of myself. Steve did.”

It’s important to note that Manuel’s not one of those anti-athlete, turd-in-the-punch-bowl types who goes out of his way to drain the air out of jocks’ egos, either. He has great reverence for athletes at Penn State and what it takes to balance books and the Big Ten and parties and being 18, living on your own for the first time.

That appreciation is a big part of why he has become an elite sports photographer that the PSU athletic department has been relying upon for almost 25 years now. In many cases, his photos have provided the visual soundtrack of Penn State sports for an entire generation of athletes, coaches, administrators and fans. If you’ve celebrated a great Penn State victory or athlete in the past quarter-century, you’ve probably spent time with Steve Manuel’s work.

It’s more that Manuel is one of those rare people who walks the earth and genuinely doesn’t seem to want or need your approval, which makes you want to get his. He doesn’t have much time for ego inflation or deflation or chasing clout, so whether you’re Penn State’s quarterback or aren’t aware the school has a football team, you’re starting from the same place with him. Like so many other people who’ve crossed paths with Manuel, that pulled Robinson in.

He wasn’t sure what Manuel would say about him, Hali and Zemaitis sitting in on class. But he enjoyed calling Manuel because he just knew there’d be no sugarcoating, no him-hawing, just straight talk. He could just ask the question and get an answer.

And besides, this call was a helluva lot easier than the one he’d made the year before, right after Robinson had been in a fight at a frat house well after midnight. Back then, he’d consulted with Manuel about the best way to handle what became front-page news across Pennsylvania—Robinson had intervened in a fight and ended up getting pushed into a glass case, requiring 24 stitches behind his ear.

News leaked out, and for the most part framed Robinson as being in the middle of a bad situation, but not as an instigator. No charges were filed. He was put on academic probation and the Penn State coaching staff made him work out every day at the same time—about 4 a.m.—he’d been in the fight. But otherwise, the incident came and went.

But when Robinson called Manuel for his perspective after the fight, he had some tough words for the quarterback. “He definitely wasn’t shy about letting me know how bad I messed up,” Robinson says. “He said something like, ‘The news cycle will be what it is, and you’ll have to own that, both publicly and personally. Even if this doesn’t continue in the papers and on the news, you need to look at yourself and what your standards are for you, when the cameras aren’t on. If you learn from this, if you really, truly learn from this, you will have a chance to redeem yourself.’”

On the way to the hot seat, Hali and Zemaitis still couldn’t believe they were attending a class they weren’t actually in. “What the hell are we doing?” Hali asked.

“This will be interesting,” Robinson said for what felt like the 100th time. “I promise.”

He was right. What they were about to witness ended up being the wildest class any of the three had ever sat down in.

“He said something like, ‘The news cycle will be what it is, and you’ll have to own that, both publicly and personally. Even if this doesn’t continue in the papers and on the news, you need to look at yourself and what your standards are for you, when the cameras aren’t on. If you learn from this, if you really, truly learn from this, you will have a chance to redeem yourself.’”

Michael Robinson

BACK IN 2013, Brian Siegrist left Penn State to take a job at South Florida in the sports information department. It was a tough decision. Siegrist loved Penn State and had put in 18 years. State College was his home. His coworkers were his friends—including Steve Manuel.

They’d crossed paths many times over the years, with Siegrist using Manuel for photography of the various sports teams Siegrist worked with during his time on campus. Siegrist always admired the way Manuel carried himself. He would cruise the hallways of the communications department, popping in and out of offices. He’s a rare blend of someone who isn’t shy but isn’t a loudmouth, either, and isn’t full of himself or full of sh--. Manuel would listen and offer suggestions and advice, but only if asked. Manuel is 5-foot-5 these days—he says he recently discovered he’d somehow shrank an inch during the pandemic—but he stands with his chin up, eyes in contact with yours, and when he speaks, it’s with a direct, steady tone. He says things and you believe him, and it sure seems like you’re talking to a 6-foot-5, 35-year-old who knows stuff.

Siegrist left State College that summer and found himself on a deserted island of sorts. He knew he’d made the right decision in taking the South Florida job, but he had no friend network and no trusted confidants in the athletic department yet. He didn’t even know where to grab some good grub at first.

And then he got some terrible news: The football team’s longtime photographer had died of a heart attack. Siegrist scrambled to duct-tape together a freelancer plan for the first two games of the season, but USF played a huge game against Miami in Week 3 and he wanted to really nail his first huge game as a new SID. He knew he had to call Steve Manuel.

Siegrist caught an incredible break. Before the pandemic, Manuel hadn’t missed a Penn State football game, home or away, since 1990. So Siegrist sighed in relief when he saw that Penn State had a bye the weekend of the Miami game, and he picked up the phone to call Manuel. He had barely gotten through his windup to the pitch before Manuel said, “I’m in,” and started booking a flight.

In his head, Siegrist certainly wanted Manuel to take great photos. But he also felt a warmth inside about just having Manuel with him for a few days, an old friend in a new place. As straight-ahead and honest as Manuel is, he’s also a reassuring presence, a guy who’s seen some sh--.

The night before the game, Siegrist took Manuel to a local fish place he liked. For an hour or so, Manuel listened as Siegrist told him how excited—but anxious—his relocated life was, how he was working through some feelings of loneliness and new job jitters. Manuel ate and processed everything Siegrist was saying, and at the end, simply said, “You’ll be all right down here.”

The day of the game, Manuel met up with Siegrist on the field and they talked for a few minutes in the pregame. Like so many other times he’d worked with Manuel, Siegrist marveled at the way he lugged around something like 30 pounds worth of gear, in hot or cold (though Manuel prefers hot), while maneuvering up and down the field, over and over and over again.

Siegrist also noticed Manuel was already in the midst of the tactical scope-outs he always does at stadiums—like something out of one of the Bourne movies, Manuel has an ability to scan physical locations, spotting exits and shortcuts and where the sunlight is and where it will be in the third quarter. On that day, Manuel had already introduced himself to a few key security people on the field, too, and so an hour before kickoff, it was like Manuel had been shooting South Florida games for 10 years. He was an honorary Bull.

The game didn’t go well, with Miami winning 49-21. Siegrist has mostly vague memories of the day—“It was hot and we got beat,” he says—but his recall of Manuel’s impact is crystal clear. By the end of the weekend, he’d come to believe what Manuel said to him at dinner: Everything was going to be okay. “To have somebody who’s a friend, somebody you knew you could rely on show up for you … that was huge,” he says. “Steve Manuel. What a dude.”

Steve Manuel gets a second opinion on a photo from the Nittany Lion.

ON THE DAY OF THE HOT SEAT, Robinson, Hali and Zemaitis arrived and sat with about 25 other students for Manuel’s one-of-a-kind exam.

The Hot Seat features several PR students who have about a month to prepare for the most excruciating 8-10 minutes of their college career. Each is given a terrible incident to be a spokesperson for (think: terrorist attacks, shootings, etc.) and has a month to prepare. It probably sounds scary … and it is. “The Hot Seat is one of the most feared classroom exercises at the entire university,” says Poorman.

The student has to stand in front of two dozen or so journalism students who are being graded on how good their questions are. So the crowd (including Robinson, Hali and Zemaitis back in 2006) is incentivized to throw fastballs, and they do. To make it even more realistic, Manuel has cameras and bright lights aimed at that day’s Hot Seat students, who take questions one at a time and aren’t allowed to listen in on mock press conferences that happen before them. It’s a daunting challenge, one that ended a few years ago with a student picking up his notes, storming from the podium and yelling, “I’m done with you” over his shoulder. He dropped the class.

But it’s also revered by those who get through it. The Hot Seat is a valuable tool for aspiring communications students in seeing what their worst, but most important, moment might look like out in the field. That’s why when Manuel says that he’s had students puke, walk off and change majors afterward, he doesn’t say it to gloat or with sadness—he thinks that’s exactly what makes the test so beautiful. “Steve wants you to be prepared and do well,” says Jessica Handler (’10), who took three courses with Manuel and now serves as director of national marketing solutions for Learfield IMG College. “He thinks if you’re aware of the worst-case scenarios and how to react to them, then you have a real chance of having an effective response.”

She pauses for a moment and laughs. “But he also wants to scare you,” she says. “He hopes you do well. But it also brings him great joy to scare you.”

On the day the football players attended, the first student approached the lectern and started fielding questions. The typical Hot Seat consists of somewhere north of 30 questions, depending on how well-prepared the spokesperson is. And in these sorts of difficult press conferences, it certainly doesn’t hurt to be able to take a small amount of information and turn it into a large number of words.

Manuel has two absolute rules. First, he allows for each Hot Seater to dodge two questions with a “No comment,” but no more than two. His second requirement is absolutely no lying—of any kind.

This student’s Hot Seat was a dumpster fire within the first 30 seconds. Robinson asked the first question, and she lied. It was so blatant and painful that Manuel’s head jerked up in surprise, and Robinson noticed. He made a career out of football on noticing a linebacker’s lean or a safety’s overreaction, and in this instance, Robinson could read Manuel’s mind.

Robinson and the other players pounced, drilling down on the lie with follow-up questions that produced another lie, and then another, and then just a flat-out scramble to create a fiction parading as fact in front of the journalism students. By the end, the student had told, by Manuel’s count, about 30 lies as she limped to the end of an ugly eight minutes. “All three of them went for the jugular,” Manuel says. “She went down like a plane on fire, spiraling out of control. She kept making up answers and it got worse and worse.”

As Manuel finishes up talking about that scenario, he hesitates for a moment when asked if he feels bad when that happens. He’s not the warmest guy in the world, he admits, but he’s not cold, either. He talks through the math he’s doing in his head about his feelings when kids get up and struggle through the Hot Seat, and it’s not an easy answer.

He ultimately says he never enjoys seeing a student whiff—he doesn’t want anybody to fail. But he also wants to do his job as an educator, which he views as giving them the realest look at what a career would resemble in what can be a difficult field. “I wouldn’t say I feel bad,” he says, then he’s silent for a second or two. “I would say I feel like I do try to scare them a little bit. But it’s about getting them to think, not to have fun at their expense. Like, is this what they really want to do? Because this is what it looks like. I feel like afterward, I give them constructive criticism. And if they want, I will go through the video with them and go through every question and answer.”

When he looks back on that day with the football players, he isn’t so much poking fun as feeling like the Hot Seat had done a service to somebody in their early 20s trying to figure out if the public relations field was right for them. Robinson felt the same way, looking back. “It was a harsh couple of minutes,” he says. “But I bet that student went one of two ways. One is, she went back to the drawing board and looked into a different career path. Or the other is, she took the L and decided to dig back in and get better. I know I always learned a lot more from losses than wins.”

Later on during the call, Robinson’s words slow down and have a tinge of pain in them as he says it’s been a while since he caught up with Manuel. At first, he thinks it’s been a year or two, but then Robinson keeps rewinding and seems stunned when he realizes it’s been at least five years, maybe closer to 10 years, since he and Manuel last spoke. He seems surprised by that, which is probably a testament to the way students digest and remember Manuel: He is such a sturdy, consistent man that you always knew where you stood, which means you still know where you stand.

Robinson is a budding media star, and as he raves about Manuel’s impact on his life, it’s easy to see and hear. Robinson lasted eight years in the NFL after being humble enough to assess his football prospects and switch from quarterback to fullback—how many times has that happened in the history of football? He loves the sport, and talks about it in an appreciative way, but he also doesn’t shy away from discussing concussions, the lack of diversity in the coaching ranks, or any other topic that many ex-players might avoid.

He isn’t trying to be a must-get hot-taker, but he’d like to be what would have gotten an A in the Hot Seat—somebody who can stand calm in the lights and say the truth, even if the truth isn’t heart-warming. “Steve Manuel helped me find my voice,” Robinson says. “I will always appreciate him for that.”

@RyanHockensmith

@RyanHockensmith